You may (or may not) have just recovered from complying with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Get ready for another round of adjustments to your privacy practices. The EU ePrivacy Regulation could mean big changes to how your company advertises online.

The ePrivacy Regulation will introduce new rules about cookies, direct marketing, and business-to-business (B2B) communications. Online advertisers have lobbied fiercely against many of its provisions. However, the proposals have changed a lot over a series of drafts.

Let's take a look at how the ePrivacy Regulation is likely to affect businesses.

- 1. Understanding the ePrivacy Regulation

- 1.1. What's the Difference Between a Directive and a Regulation?

- 1.2. Will the ePrivacy Regulation Replace the GDPR?

- 1.3. When Will the ePrivacy Regulation Come into Force?

- 2. The ePrivacy Regulation and Cookie Consent

- 2.1. Less Strict Rules on Cookie Consent

- 2.2. Cookie Walls

- 2.2.1. What is a Cookie Wall?

- 2.2.2. Why are Cookie Walls a Problem?

- 2.2.3. Will the ePrivacy Regulation Allow Cookie Walls?

- 2.3. Browser-Based Opt-Outs

- 3. The ePrivacy Regulation and Direct Marketing

- 3.1. Electronic Marketing Without Consent

- 3.1.1. The Soft Opt-In

- 3.1.2. Will the Soft Opt-In Survive?

- 3.2. B2B Direct Marketing

- 3.2.1. Natural Persons and Legal Persons

- 3.2.2. Is Consent Required for B2B Direct Marketing?

- 4. Summary

Understanding the ePrivacy Regulation

The ePrivacy Regulation will replace the ePrivacy Directive (sometimes known as the "Cookies Directive"), which has been law since 2002.

It's worth noting that, like the ePrivacy Regulation, the GDPR is also a regulation that replaced a directive (the Data Protection Directive). The impact of this change is likely to be equally significant in certain sectors.

What's the Difference Between a Directive and a Regulation?

So, while the old law was a directive, the new law will be a regulation. What's the difference, and why is this changing?

A directive is a set of objectives that EU Member States (EU countries) must meet. A directive is addressed to Member States. It describes the sorts of national laws that Member States must pass. Then it's up to the Member States to pass those laws.

A regulation goes directly into effect in Member States. There's generally no need for Member States to pass national laws to give effect to a regulation. However, sometimes Member States are required to pass national laws to implement certain parts of the regulation.

If the national law of a Member State contradicts an EU regulation, the regulation takes priority.

The ePrivacy Directive is imposed differently across Member States. For example, in the UK's version is the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations (PECRs). In Ireland, somewhat confusingly, it's called the ePrivacy Regulations (available here).

These national laws are all different. So a regulation will make things simpler for businesses that operate across borders or deal with businesses from multiple EU countries.

As European Commissioner Andrus Ansip puts it:

"All this will mean the same level of protection for everyone in the EU. It also cuts red tape for European businesses. They will have just one set of rules to deal with, not 28."

It's worth noting, however, that the ePrivacy Regulation does allow Member States to implement some rules differently at national level. Each draft seems to afford Member States greater flexibility.

Will the ePrivacy Regulation Replace the GDPR?

The ePrivacy Regulation will not replace the GDPR. It's designed to complement the GDPR.

The GDPR provides a broad framework for all activities involving the processing of personal data. The ePrivacy Regulation will show how this framework applies to the area of privacy in electronic communications.

The GDPR and the ePrivacy Regulation should be compatible. But if the ePrivacy Regulation contradicts the GDPR in some way, the ePrivacy Regulation will override the GDPR.

When Will the ePrivacy Regulation Come into Force?

The ePrivacy Regulation was due to pass in May 2018, at the same time as the GDPR came into force.

The ePrivacy Regulation has been pushed back several times, and is now expected at some point in 2019. But don't hold your breath. This law is the subject of industry lobbying and institutional debate that could delay it even further.

It's also worth remembering that once the law finally passes, there's likely to be a transition period before it comes into force. For the GDPR, this was two years.

The ePrivacy Regulation and Cookie Consent

The ePrivacy Regulation will make several significant changes in the area of cookie consent. It will also unify the rules, which are currently interpreted slightly differently in different Member States.

Less Strict Rules on Cookie Consent

The current rules on cookie consent come from the ePrivacy Directive. All cookies require consent, except from those covered under an exemption.

Exempted cookies that do not require consent include those that are:

- Used to facilitate communication over a network

- Necessary to provide a service that a user has requested (e.g. "remember my username")

This means some very useful and non-intrusive cookies require consent - whether or not the cookies involve personal data. This includes cookies used for analytics (even first-party analytics), optimization and load-balancing.

The ePrivacy Regulation proposals include some new exemptions. Websites will no longer need consent for cookies that are necessary for:

- Audience measuring

- Security and fraud prevention

- Debugging

- Providing software updates

- Locating a device in an emergency

All of these exemptions will be subject to restrictions, for example on how long the cookie can be stored. But these proposals appear less strict than the current law.

Tracking cookies (and other tracking technologies such as web beacons) will still require consent.

Cookie Walls

"Cookie walls" are a particularly controversial way of getting cookie consent. Some Member States, such as Sweden, allow cookie walls under national law.

What is a Cookie Wall?

A cookie wall is a cookie banner that denies access to a visitor access to a website unless the visitor consents to cookies.

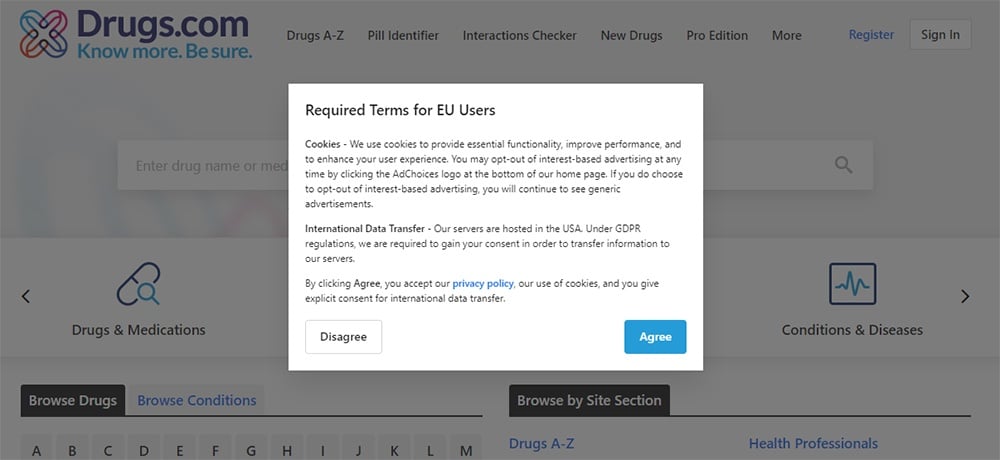

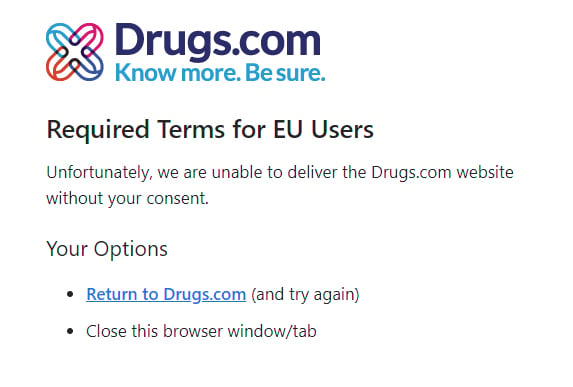

Here's an example from Drugs.com:

The site isn't accessible beneath the cookie consent mechanism. To use the website, a visitor must consent to advertising cookies. Drugs.com does inform the visitor that they can opt-out once they've consented.

Here's what happens if the visitor clicks "Disagree":

Why are Cookie Walls a Problem?

There are mixed views on cookie walls. On one hand, many consumers might be willing to "trade" their personal data for access to an online service. Also, many businesses depend on advertising revenue. This revenue can be increased by using tracking technologies.

On the other hand, such consent mechanisms do, arguably, contradict the GDPR's requirements around consent. There's a good reason to define consent as freely given. Recital 42 of the GDPR says that:

"Consent should not be regarded as freely given if the data subject has no genuine or free choice or is unable to refuse or withdraw consent without detriment."

The European Data Protection Board has given a statement about cookie walls, arguing that consent earned via a cookie wall is not valid.

Will the ePrivacy Regulation Allow Cookie Walls?

It appears that the ePrivacy Regulation will allow cookie walls under certain conditions.

A May 2018 draft of the ePrivacy Regulation explicitly permitted cookie walls for all websites providing a non-essential service (e.g. Government websites). Recital 20 of this draft stated that:

"Access to specific website content may still be made conditional on the consent to the storage of a cookie or similar identifier."

This section was replaced in a February 2019 draft of the Regulation. This draft suggests that a cookie wall could be acceptable if the user is given a choice between paying for a service or consenting to cookies.

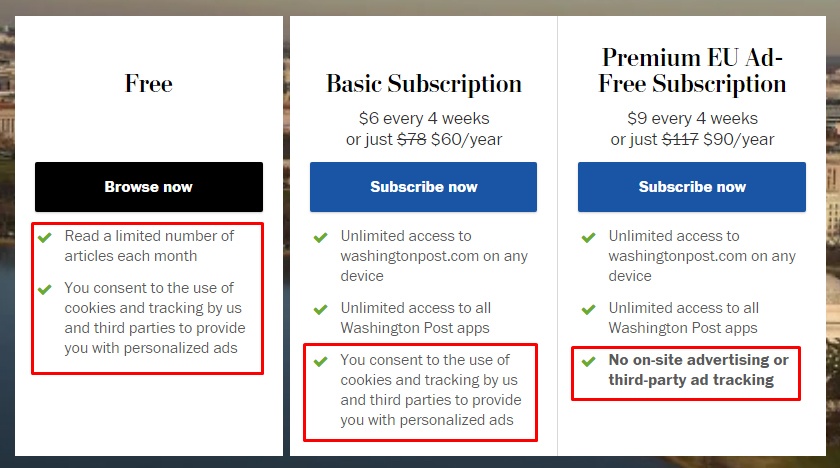

Certain companies already do this. For example, here's what greets EU visitors to the Washington Post:

EU visitors to the Washington Post website have the option to consent to cookies or pay a subscription.

This model of cookie consent is problematic under the current law. You must implement a cookie consent solution and maintain a Cookies Policy that complies with the ePrivacy Directive and the GDPR.

However, cookie walls that offer a paid alternative to consent, like the Washington Post's, could be permitted under the ePrivacy Regulation. Cookie walls that offer no alternative to consent are likely to be forbidden across the whole of the EU.

Browser-Based Opt-Outs

If you want to use tracking cookies, some sort of cookie banner is required by law. However, they unpopular among some people. The ePrivacy Regulation will bring some changes regarding how users consent or object to cookies via their browser settings.

Early drafts of the proposals would have forced browser software companies to explain cookies to their users during the setup process. Users could then block or consent to all tracking cookies by default.

This would have been highly problematic for online advertisers. It would also sit uneasily with the GDPR's requirement that consent is "specific."

This has been watered down in the February 2019 draft of the proposals, which states that web browser providers

"are encouraged to ensure that end users can easily set up and amend [cookie] white lists and withdraw consent at any moment in a user-friendly and transparent manner."

This should allow users to manage their cookie consents via their browser settings. But it's not likely to spell the end of online advertising as we know it.

The ePrivacy Regulation and Direct Marketing

The ePrivacy Regulation is set to bring electronic marketing under a single framework across the whole EU.

For the purposes of this section, "electronic marketing" or "marketing communications" means marketing via email, messaging services (such as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger), fax, and SMS.

Electronic Marketing Without Consent

Some people believe that the GDPR requires consent for practically all processing of personal data. This isn't true. Consent is only one of the six lawful bases for processing personal data under the GDPR.

The Soft Opt-In

The current law allows for a "soft opt-in." This allows businesses to send consumers direct marketing communications without consent under certain conditions.

Under the GDPR and the ePrivacy Directive, it's possible to send marketing communications under the lawful basis of "legitimate interests." This is only normally allowed under certain conditions:

- The person has made a purchase from you

- They gave you their contact details

- They had the opportunity to opt out when they gave you their contact details

- You send an "unsubscribe" mechanism with every marketing communication

Under some Member States' laws, it's also possible if the person has entered into "pre-contract negotiations" for a sale (subject to the last three of the above conditions).

Before you can rely on the lawful basis of legitimate interests, you'll also need to conduct a Legitimate Interests Assessment.

Will the Soft Opt-In Survive?

Early drafts of the ePrivacy Regulation suggested that businesses would no longer be allowed to rely on legitimate interests for direct marketing. This would have meant that all electronic direct marketing would require opt-in consent.

This is not the case in the most recent two drafts. There is a clear mechanism allowing for a soft opt-in. This means that businesses will continue to be able to send marketing communications to their existing customers, without consent, where the soft opt-in conditions are met.

There is no mention of "pre-contract negotiations" in the proposals. This sounds like a minor omission. However, it could be significant in countries, like the UK, where national law allows businesses to send marketing communications to potential customers under certain circumstances.

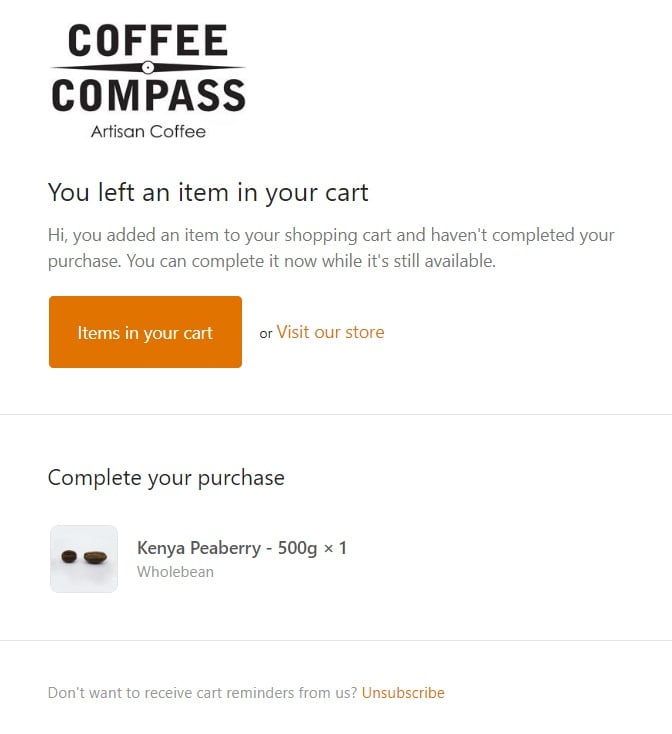

To put that into context, take a look at this email from Coffee Compass:

This email alerts the customer that they have not completed a sale that they may have intended to complete. This sort of marketing email is permitted under the ePrivacy Directive in some EU Member States, even if the customer has not previously made a purchase from the company.

Under the proposed ePrivacy Regulation, communications like this would no longer be allowed without consent, unless the customer previously had made a purchase from the company.

The proposals could also make the soft opt-in narrower. Member States will be able to assign a time-limit, beyond which companies would not be allowed to rely on the mechanism.

This would mean that if you sold a person something a long time ago, you would no longer have the right to send them marketing communications without their consent. Member States could each define how long this period would be under their national law. After this time limit elapses, you'll need to remove the customer from your marketing lists or obtain their consent.

B2B Direct Marketing

The ePrivacy Regulation would expand into some uncharted territory - the realm of business-to-business (B2B) marketing.

Natural Persons and Legal Persons

The GDPR only protects "natural persons." This means identifiable, living individuals. It's all about "personal data," which is data about natural persons.

The GDPR doesn't protect "legal persons." A legal person is an entity with certain legal rights. It can enter into contracts, take you to court, and lobby the government. But it's not a human.

So, for example:

- Google is a legal person. Google's CEO, Sundar Pichai, is a natural person.

- Calvin Klein, the corporation, is a legal person. Calvin Klein, the fashion designer, is a natural person.

The GDPR sets rules for both natural persons and legal persons. But it only protects personal data. Sundar Pichai and Calvin Klein (the fashion designer) have personal data. Google and Calvin Klein (the corporation) do not.

The ePrivacy Regulation is about electronic communications. It protects the privacy of electronic communications whether they contain personal data or not. In this way, the ePrivacy Regulation protects both natural persons and legal persons.

Therefore, the ePrivacy Regulation sets rules for how businesses communicate with other businesses.

Is Consent Required for B2B Direct Marketing?

A leaked early draft of the ePrivacy Regulation suggested that all B2B direct marketing might require opt-in consent. This led to a lot of panic and heavy lobbying from B2B marketing companies.

This is not true in the most February 2019 draft. But the rules are changing.

To understand the new rules, consider the difference between sending direct marketing emails to the following three email addresses:

The current rules apply to email addresses 1 and 2. These both contain personal data - even though 2 is a corporate account. So, even if you're sending B2B communications to email addresses 1 or 2, the owner has rights under the GDPR since you are processing their personal data.

The current rules don't cover email address 3. This is non-personal data belonging to a legal person.

The February 2019 draft of the proposals would not require consent for all B2B direct marketing. However, businesses will need to respect the "legitimate interests" of legal persons. The Regulation would allow EU Member States some flexibility to make their own laws in this area.

This means that emails sent to email address 3 (above) will probably need to contain an unsubscribe mechanism.

It might also mean that unsolicited B2B direct marketing communications (without a pre-existing business relationship involved) could require consent.

Summary

The ePrivacy Regulation will have many implications for small businesses. It will:

- Bring greater certainty and consistency across the EU

- Change the requirements around cookie consent

- Impose stricter rules around consent for direct marketing in some countries

- Require businesses to take greater care when marketing to other business

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.