Clickwrap is becoming more commonly known as a legally secure and easy way of creating binding agreements with your users online.

There are a number of legal cases that have established the validity of clickwrap methods, however, and they all set out different requirements and nuances of clickwrap's use.

We're going to look at three of these key legal cases, what they mean for business owners and website operators, and how to comply.

First, let's look at what clickwrap is.

What is clickwrap

Clickwrap is a method of getting legally binding agreement to your legal documents. It means that the user has actually clicked "I Agree" to the Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy or shown that they explicitly agree in some way.

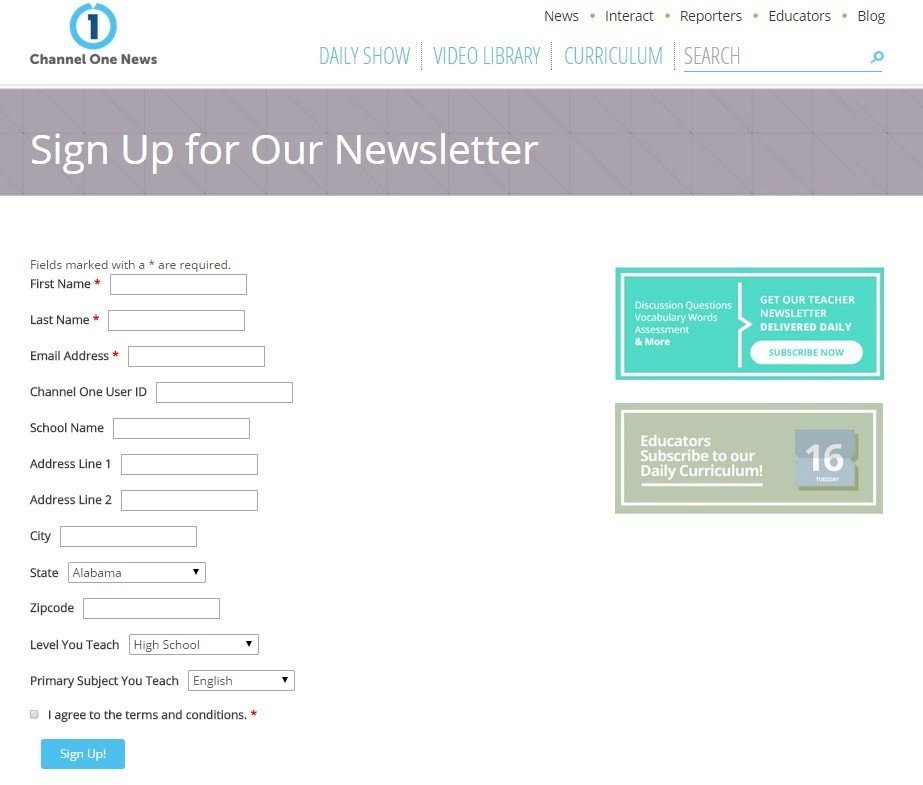

Here's an example of what clickwrap looks like from Channel One News newsletter sign-up:

You can see the check box at the end of their web form saying "I agree to the terms and conditions". Once we've looked through the three key legal cases below, see if you can spot what is missing in the above clickwrap example.

This is in contrast to browsewrap, which is where the user does not click "I agree" to anything, and instead is simply presumed to have agreed to the terms by implication: implied agreement.

The terms are usually displayed at the bottom of the webpage and the user must browse to read them. There is no certainty or indication at any point from the user to the website owner that the user has read the terms.

This is what browsewrap looks like, from Ars Technica website footer:

You can see that the terms are highlighted in orange down the bottom in small print.

The 3 legal cases

Now let's look at three key legal cases in the US that have looked at clickwrap and its enforceability.

Feldman v Google

One of the most high-profile cases on the matter was Feldman v. Google, Inc., 513 F.Supp.2d 229 (E.D.Pa. 2007).

Feldman v Google was a case that involved Lawrence E. Feldman & Associates (Feldman) who purchased advertising from Google's "AdWords" Program.

Feldman argued that he was the victim of "click fraud", which is when entities or persons, without any interest the services being advertised, click repeatedly on ads. This has the result of driving up the advertising cost.

Feldman claimed that Google required him to pay for all clicks on his ads, including those which were fraudulent. The subject that was at issue, in this case, was the forum selection clause in their agreement -- i.e., the clause that covered where any dispute resolution would take place.

The clause read:

The Agreement must be construed as if both parties jointly wrote it, governed by California law except for its conflicts of laws principles and adjudicated in Santa Clara County, California.

Feldman claimed that the Agreement "was neither signed nor seen and negotiated by Feldman & Associates or anyone at his firm".

Feldman was required to enter into an AdWords contract before placing any ads or incurring any charges. At the top of the page displaying the AdWords contract, a notice in bold print appeared and stated, "Carefully read the following terms and conditions. If you agree with these terms, indicate your assent below."

The terms and conditions then appeared. The preamble (shown at the top of the Agreement), stated that by agreeing to the terms listed in the Agreement, a binding agreement with Google would be formed.

At the bottom of the web page, viewable without scrolling down, was a box and the words, "Yes, I agree to the above terms and conditions." Feldman had to have clicked on this box in order to proceed to the next step. As he had activated his account, placed ads, and incurred charges, it was clear that he had clicked on this box.

The Court cited Baer v. Chase 2006 to say:

Contracts are 'express' when the parties state their terms and 'implied' when the parties do not state their terms. The distinction is based not on the contracts' legal effect but on the way the parties manifest their mutual assent. [...] To determine whether a clickwrap agreement is enforceable, courts presented with the issue apply traditional principles of contract law and focus on whether the plaintiffs had reasonable notice of and manifested assent to the clickwrap agreement.

In this case, the Court concluded that Feldman had reasonable notice of the terms, and manifested assent to the agreement. The Judge noted:

The user here [Feldman] had to take affirmative action and click the "Yes, I agree to the above terms and conditions" button in order to proceed to the next step. Clicking "Continue" without clicking the "Yes" button would have returned the user to the same webpage. If the user did not agree to all of the terms, he could not have activated his account, placed ads, or incurred charges

As a result, the clickwrap agreement was upheld.

Specht v Netscape Comms. Corp

So now that we've established if you use a tick box or button for your users to agree, you're sorted, right? Not quite.

Specht v. Netscape, 306 F.3d 17 (2d Cir. 2002) set out that it's not just the tick box or "I Agree" button that's important, it's also that the terms need to be conspicuous, and it needs to be clear that the tick box or button relates to the agreement to the terms (rather than something else).

Specht v Netscape was a case between a number of plaintiffs (including Mr Specht) (the Plaintiffs) and Netscape Communications Corporation (Netscape). The Plaintiffs had all installed a Netscape program called SmartDownload. SmartDownload transmitted personal information to Netscape when the Plaintiffs used it to browse the Internet.

The Plaintiffs argued that this had invaded their privacy, and they brought a lawsuit against Netscape. Netscape argued that the Plaintiffs had agreed to an arbitration clause in license terms that they had (allegedly) accepted when they downloaded SmartDownload.

The Court's role was to determine whether the Plaintiffs had agreed to be bound by the software's license agreement.

On the page to download SmartDownload, a "Download" button was displayed with the text "Start Download". Below the fold of the page, if the Plaintiffs had scrolled down they would have seen a statement saying:

Please review and agree to the terms of the Netscape SmartDownload software license agreement before downloading and using the software.

The license agreement contained a clause stating:

BY CLICKING THE ACCEPTANCE BUTTON OR 10 INSTALLING OR USING NETSCAPE COMMUNICATOR, NETSCAPE NAVIGATOR, OR NETSCAPE SMARTDOWNLOAD SOFTWARE (THE "PRODUCT"), THE INDIVIDUAL OR ENTITY LICENSING THE PRODUCT ("LICENSEE") IS CONSENTING TO BE BOUND BY AND IS BECOMING A PARTY TO THIS AGREEMENT

But this statement was not displayed or indicated anywhere the "download" button for SmartDownload.

The Court concluded that:

Although an onlooker observing the disputed transactions in this case would have seen each of the user plaintiffs click on the SmartDownload "Download" button [...] a consumer's clicking on a download button does not communicate assent to contractual terms if the offer did not make clear to the consumer that clicking on the download button would signify assent to those terms. [...] California's common law is clear that "an offeree, regardless of apparent manifestation of his consent, is not bound by inconspicuous contractual provisions of which he is unaware, contained in a document whose contractual nature is not obvious."

As a result, the Plaintiffs were not bound by the terms of the license agreement as the agreement was too inconspicuous. The "Download" button was not sufficiently related to the terms of the agreement for the Plaintiffs to be legally bound by it.

Bragg v Linden Research, Inc.

This case, Bragg v. Linden Research, Inc., 487 F. Supp. 2d 593 (E.D.Penn. 2007), was between Linden Research, Inc (Linden), the creators of the game Second Life, and Mr. Bragg, a Second Life player. Second Life is an online virtual world game in which players can build objects, explore the world, and interact with other players. Players can also purchase land with real life money.

In November 2003, Linden said that it would recognize participants' full intellectual property protection for the digital content they created or otherwise owned in Second Life, such as "cars to homes to slot machines." Players were also able to purchase "virtual land," make improvements to that land, exclude other players from entering onto the land, rent the land, or sell the land to other players for a profit.

Bragg had purchased numerous parcels of land in his Second Life, including a parcel of virtual land named "Taesot" for $300. Linden sent Bragg an email advising him that Taesot had been improperly purchased through an "exploit" and as a result Linden took Taesot away. It then froze Bragg's account, effectively confiscating all of the virtual property and currency that he maintained on his account with Second Life.

Like Specht v. Netscape, when Bragg sued Linden in Court, Linden argued that their agreement required arbitration to occur.

Before a person is permitted to participate in Second Life, they must accept the Terms of Service of Second Life by clicking a button indicating acceptance. Bragg conceded that he clicked the "accept" button before accessing Second Life. Bragg resisted enforcement of the TOS's arbitration provision on the basis that it was "both procedurally and substantively unconscionable".

In Californian law, the procedural component can be satisfied by showing:

- Oppression through the existence of unequal bargaining positions

- Surprise through hidden terms common in the context of adhesion contracts

The substantive component can be satisfied by showing overly harsh or one-sided results that "shock the conscience."

The Court stated that a contract is procedurally unconscionable if it is a contract of adhesion. A contract of adhesion is a "standardized contract, which, imposed and drafted by the party of superior bargaining strength, relegates to the subscribing party only the opportunity to adhere to the contract or reject it."

In this case, the Second Life Terms of Service were a standardized contract which only allowed the customer to agree to it or reject it.

The Court held that:

When the weaker party has presented the clause and told to 'take it or leave it' without the opportunity for meaningful negotiation, oppression, and therefore procedural unconscionability, are present. [...] An arbitration agreement that is an essential part of a 'take it or leave it' employment condition, without more, is procedurally unconscionable.

But surely there's a problem here - we all know that standard form contracts are used all the time!

Here's the reason: If there are numerous providers of the same service, such as e-commerce websites, contracts of adhesion are not at issue, as a customer can always go to another vendor if they don't like your terms of service. In this case, there was no alternative to Second Life in the market.

So, to put it simply, if Mr. Bragg did not accept these terms, he could not play Second Life or any other similar game or service, which created an unconscionable take-it-or-leave-it situation. Linden also had superior bargaining strength over Mr. Bragg, and the contract was, therefore, a contract of adhesion.

What these cases mean for your business

There are 3 main take away points for you:

First, make sure that your customers have manifested assent to your agreement by using a check box or "I agree" button to gain acceptance.

Second ensure that the contractual nature of your agreement is obvious and that the agreement is not inconspicuous.

Your customers must be able to have reasonable notice and an opportunity to review your terms. Part of this means that your terms must be easy to read. If your terms are difficult to read and hidden amongst legalese, it may be held by a Court that your users did not have reasonable notice of them.

Finally, if you are a one-of-a-kind service provider, ensure that your terms are drafted fairly and reasonably, and ensure that you provide take-it-or-leave-it terms where users have no choice but to agree. If you are not a one-of-a-kind service provider, still ensure that your terms are fair and reasonable.

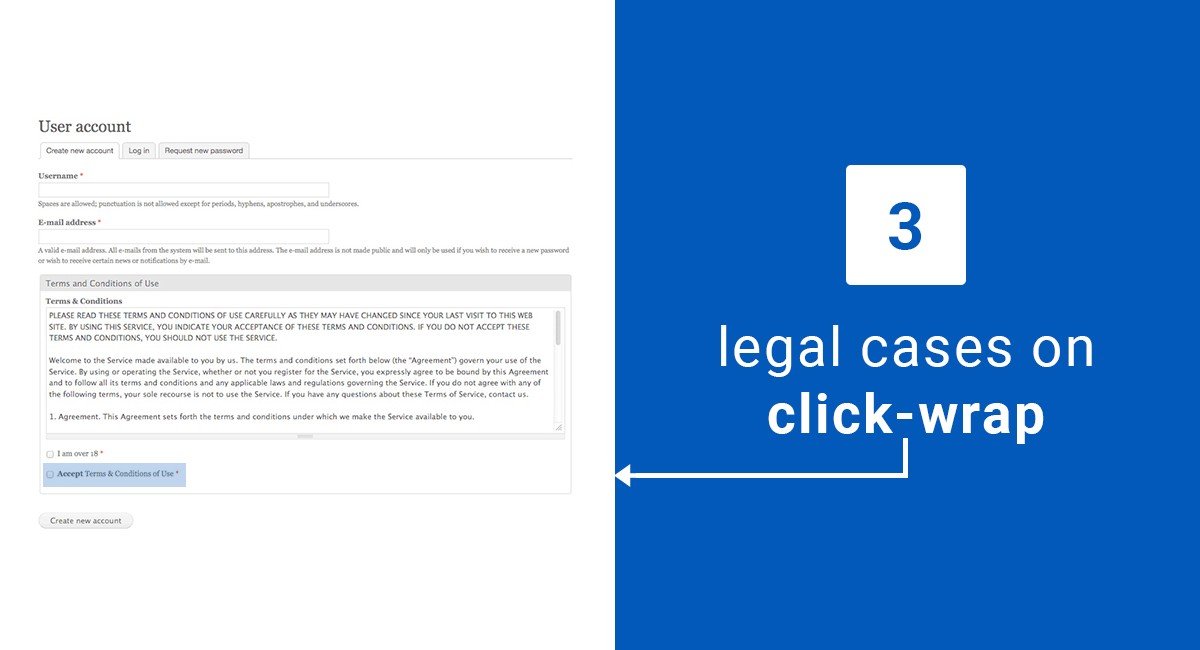

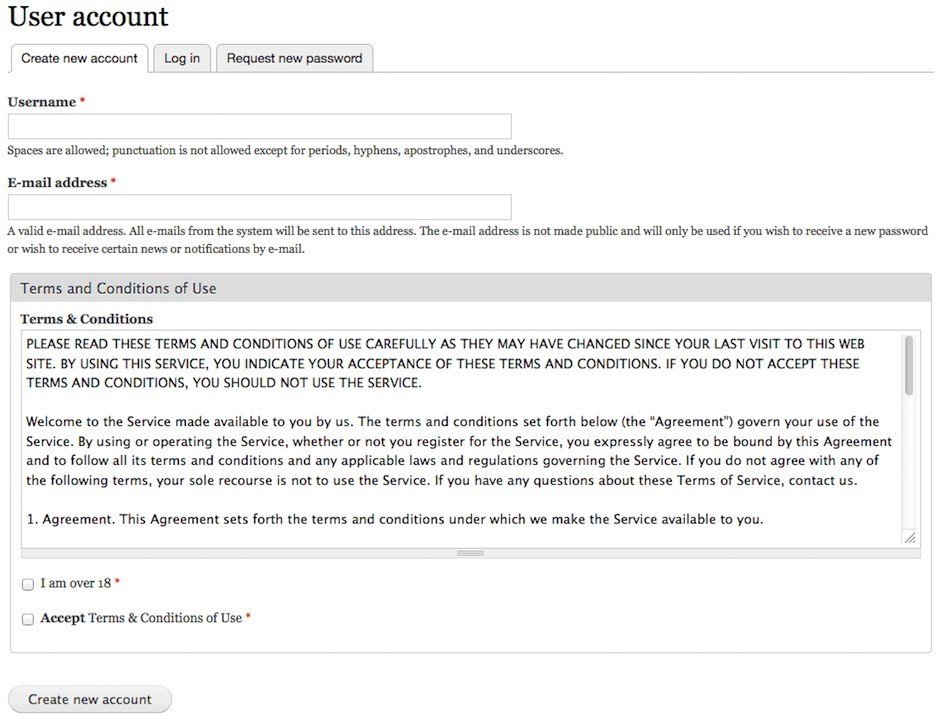

The clickwrap example up above was not quite right for one key reason. They did have a tick box to agree, but they didn't link to their terms or display their terms clearly Here's an example of what a clear clickwrap agreement should look like from Drupal.org:

You can see that this clickwrap method is stronger, as it includes a tick box but also includes the Terms and Conditions right there for the user to read.

A clear link to the terms is also acceptable, but this method makes it obvious and easy for the user to read through the terms before they click "I Agree".

Clickwrap contracts are the strongest way to obtain legal agreement online, but there are still pitfalls that you need to be aware of before setting these up.

Now that we've looked at the above cases and gone through some of the key tips, you should be able to set up a fair clickwrap agreement that is prominently displayed, easy to read, and cannot be struck down by a Court.

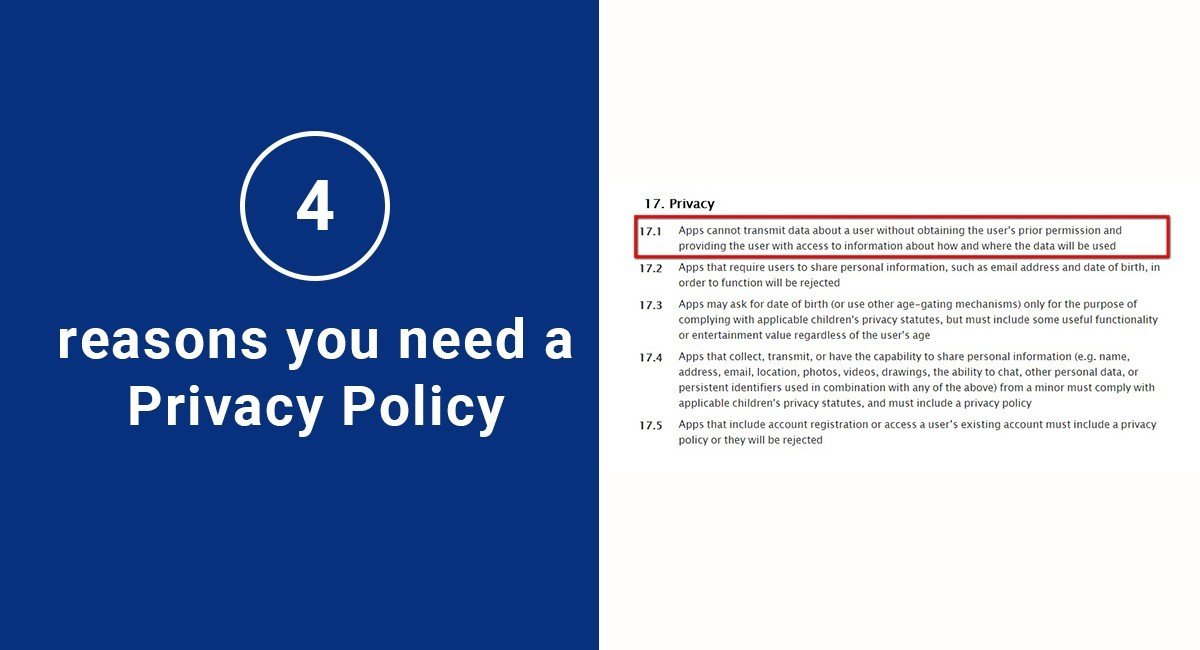

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.